When COASST was getting started, there were a whole bunch of things we wanted to know that required each bird to be uniquely tagged:

- How long do birds persist on the beach?

- What body parts last the longest (important for developing a useful beached bird guide)?

- Do scavenging rates vary?

- Once beached, can carcasses move from beach to beach?

What we now know is that the first time a beached bird is found on a COASST survey is usually the last time. After a brief interruption of measurement, photography and tagging, the natural processes of scavenging, decomposition, burial and tidal action take their course. A month later, only 19% of the 75,778 new birds found by COASSTers, have ever been seen again.

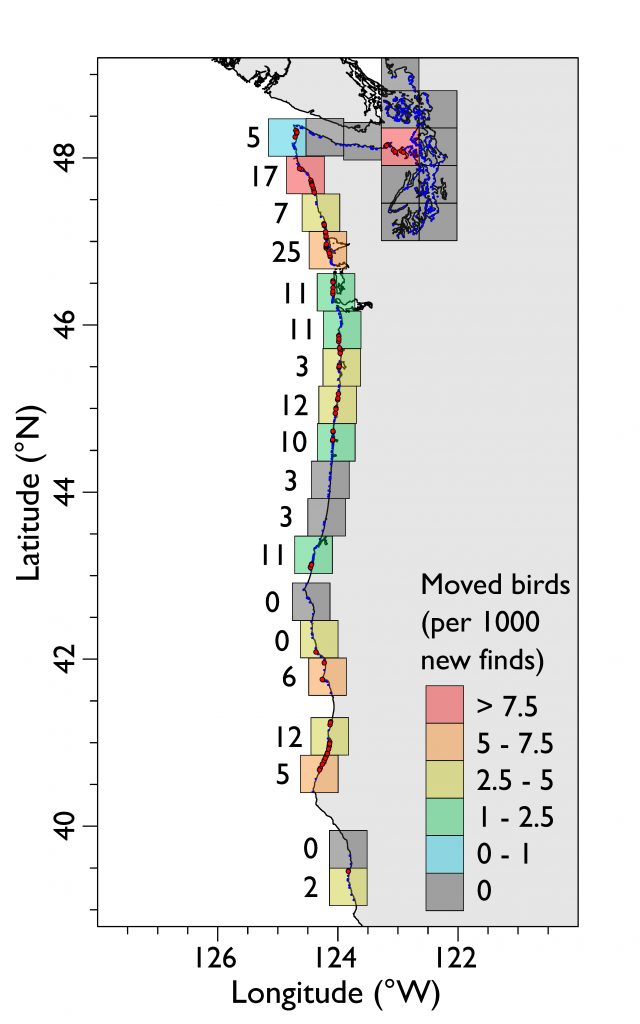

We also learned that it’s truly rare for a tagged bird to subsequently be found on a different COASST beach. Just 239, or 0.3% of newly found birds, moved from one beach to another. As you would expect, there are some patterns, and these are ruled by birdiness and beach proximity.

Rule #1: The more birds you have the more likely you are to see one move. For instance, 20% of the moving birds coincided with wrecks like the Scoter die-off along the outer coast of Washington in 2009 and the massive Cassin’s Auklets mortality event along the Washington-Oregon coastline in 2014-15.

Rule #2: The more beaches are squished together, the more likely it is that a tagged bird from one beach will show up on a neighboring beach. The map below shows movement rate within 50 by 50 km squares, calculated as the number of tagged carcasses moving from one COASST beach for every 1,000 new finds. Some places are “hot” like Dungeness Spit at the entrance to Puget Sound, or Ocean Shores in the south outer coast of Washington, or the Humboldt region of northern California. In these places, beaches are literally piled on top of each other (the number next to each square is a count of beaches that are right next to one another).

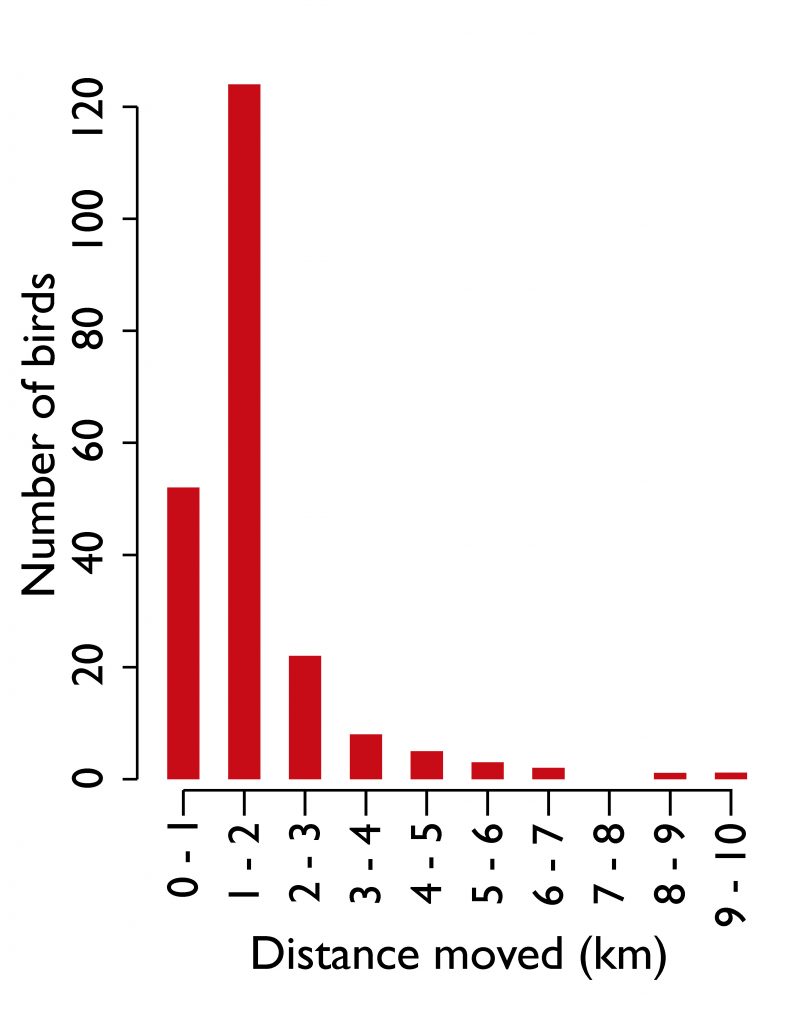

How far to the movers go? Not very far: 74% moved less than 2 km, in most cases to a COASST beach sharing a boundary. We think that scavengers likely account for the majority of birds that moved between adjacent beaches.

However, there have been a few instances where birds have moved more than 10 km,. These longer distances may well be carcasses that were washed off of one beach to be transported along the shore by prevailing wind and currents before washing in again elsewhere.

What does all of this tell us? Mainly that we can relax the rules for “starting tag number” on adjacent beaches. Up until now, COASST has assigned both a starting number, and a total sequence (e.g., 100-300) for each beach. Birdy beaches got large sequences, non-birdy beaches got narrow ones (e.g., 1-10).

While interesting, the observed movement rates are so low they are unlikely to be a major source of error in the baseline and mortality event patterns so visible in the COASST dataset. Armed with this information, we’re very excited for new possibilities in bird tagging.

Colored zip ties have worked extremely well as a cheap, efficient way of uniquely tagging birds. But from a sustainability and environmental friendliness standpoint, they leave something to be desired even if we minimize plastic by clipping the tails off. As many of you know, COASST headquarters has been busy scheming-up alternatives for the last couple of years, and some COASSTers have helped us pilot and critically review more sustainable candidates. Hemp and jute twine; organic wool yarn, metal tags – we’ve looked at, and tested, many possibilities to find that perfect balance of environmentally sustainable, easy to use, stays on and stays readable, and not so expensive we break the bank. So stay tuned, we are nearly there!