It’s the wrack zone that’s so difficult to figure out—where it begins, where it ends. “See, there’s a piece,” says Adelia Ritchie, pointing to a short scrap of seagrass, and then another, and another. “You can see there’s sort of a whole band all along here.”

“But what about up there?” Gretchen Waymen-Palmer says. A few yards up the beach, the band of seagrass bits and pieces is a bit thicker.

“I think we should go higher, because that’s clearly the surf zone,” Ritchie says, gesturing to the small waves gently lapping the beach on this bright, sunny day.

Ritchie and Waymen-Palmer walk between the two candidate bands that could form the lower boundary of the “wrack zone”, and talk over their relative merits. One begins to sense a creeping irony in the name of this beach on the Kitsap Peninsula, near the small town of Hansville: Point No Point.

But there is a point, and an important one: To uncover whatever patterns there might be in the sourcing and impact of marine debris, so they can be acted on to prevent and manage the stuff. That is why, in 2014, COASST developed the marine debris module.

Today’s survey started at the Hansgrill, a nearby cafe where Ritchie, who goes by Dee, met up with Waymen-Palmer, and Sheryl and Todd Ramsey to plot strategy over an early lunch. Then they were off to the point. It was Sheryl’s turn to pace, and to get to the first randomly generated spot—they would ultimately do four over 1,500 meters of beach—she had go 606 paces.

So Sheryl set out from the parking lot . Once she reached the pre-determined footfall, Todd stretched out a rope five meters long with the spot as its center, creating a vertical strip (or sampling rectangle, in COASST terms) from the top of the beach down to the water. The strip was then divided into a progression of horizontal bands (or beach zones): from the vegetation just above the beach, to the jumble of wood at the top of the sand, to the bare sand, to the befuddling wrack, and last but not least the surf – places that variably hold onto and obscure our target of marine debris. The Veg, Wood, Bare Sand, and Surf bands were easy enough; the Wrack, not so much.

Ritchie and Waymen-Palmer, joined by Sheryl Ramsey—Todd is setting up small orange flags to mark the boundaries of the other zones—eventually settle on the thin band near the bottom. “Sometimes we look a little like Keystone Kops,” Ritchie says and she grabs more orange flags. “We have to, you know, wrack our brains.” She grins.

Ritchie has been a marine debris volunteer for about a year, having lived near Point No Point for a half dozen years. She has a Ph.D. in physical organic chemistry, and spent much of her career working on projects for the Department of Defense in varying capacities. (“How many chemists do you know who have gotten to ride in F-16s?” she asks at one point.) She first really noticed the issue of marine debris a couple of years ago, when a garbage scow “overturned or sank or something” near the point. Junk filled the beach to an astonishing degree, she says, “just all sorts of plastic things that really have no business being in the water.” She and her cousin, who was visiting from Canada, picked up twenty pounds of stuff. But when they went to clean more of the beach, a few property owners—save for a county park around the point, most of the beach is privately owned—shooed her away. It was their beach, their taxes, they would clean up their own trash.

Fair enough, thought Ritchie, but she was tuned in now, and started paying attention to the debris she saw on her regular walks. Shortly after, COASST happened to be hosting a training in nearby Poulsbo, and Ritchie went.

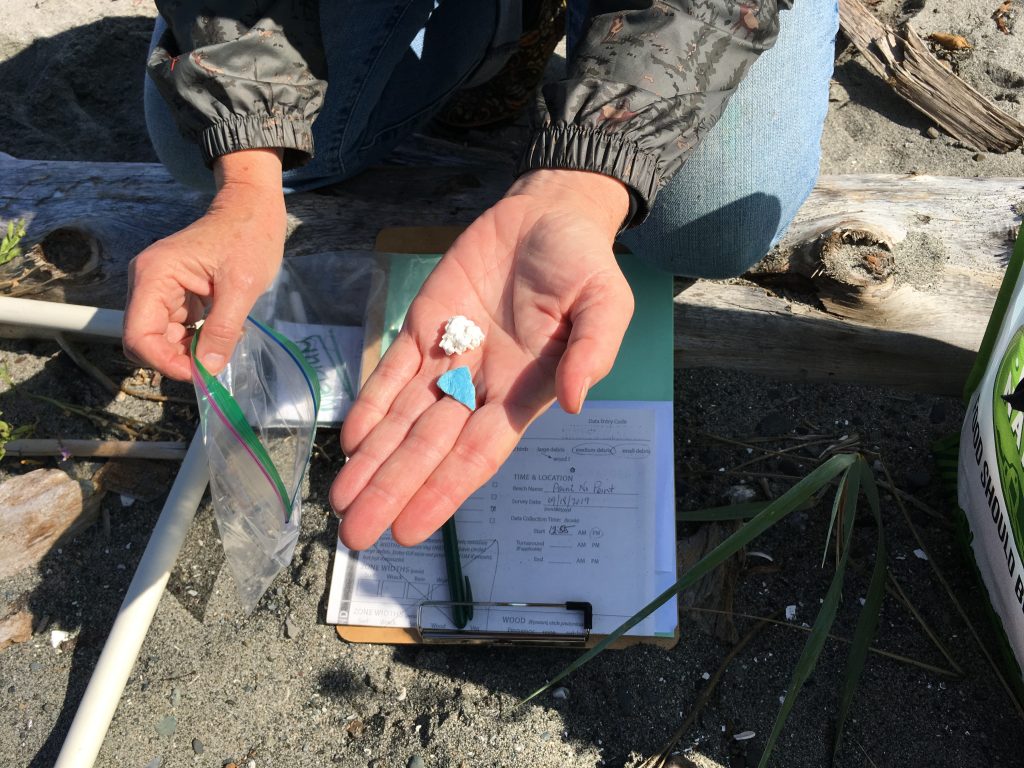

Now that the site is arranged, the survey can begin. Although marine debris surveys are concerned with debris of all sizes, Ritchie and her team deal only in medium (2.5-50cm) and small (2.5mm -2.5cm) debris; another team handles the large debris, like the lumber or occasional cargo crates that wash up. Everyone scours the different bands, collecting every piece of debris they find. Each item goes into a plastic bag, denoted by band and size.

They really have to look. It is almost as if they want to find garbage. “Surveys like this are a lot of fun,” Todd Ramsey says. “Except for all those people who go out and pick up our trash before we get here. It’s like, Hey, they’re taking all our fun!”

“People care about this beach,” Ritchie agrees. “There’s no official cleanup that I know of, but people are always picking up stuff. It’s rare for us to find small debris.”

Ritchie, Waymen-Palmer, and the Ramseys finish the strip and gather all their gear. Sheryl sets off down the beach to the next point that is 538 paces away. The four of them will do the other three strips, and then turn back for the parking lot.

Later, back at the Hansgrill, they will spread a sheet across one of the tables and unload their gatherings. Then, piece by piece, they will catalog everything: what it is (if they can tell, which they can’t always), its size, how weathered it is, whether it is made of plastic, whether it has things growing on it, whether it has loops (which animals could stick their heads through), if it has a logo or brand, and so on. When they are finished, most of this garbage will go into the trash, where it will stay there for good. But not everything. Every so often, Ritchie will come across nice pieces of beach glass among the cigarette butts and other miscellany. These she will pluck out with an exclamation of delight and tuck them in her pocket: a few more little treasures for her jar back at home.

Photos and story by COASST science writer, Eric Wagner