At 55 grams, phalaropes are among the smaller shorebirds that wash up on COASST beaches. Despite their small size, phalaropes are long-distance migrants that breed in the Arctic and head south of the equator in winter. In the lower 48, COASSTers are most apt to find a phalarope in the Fall-Winter during the southward migration; that is, right now!

Easy to identify given their distinctive multi-lobed feet, these tiny birds use their toes to help them gather food by paddling in a tight circle around and around until they produce a vortex (like a small cyclone) underneath their spinning body which sucks up zooplankton and brings prey within reach of the long needle-like bill. Lucky kayakers out for a fall paddle along tidal rips can be surrounded by hundreds of spinning birds intent on fattening up before continuing south.

The vast majority of the phalaropes COASSTers encounter are Red Phalaropes. A smattering of Red-necked Phalaropes have also been found over the years.

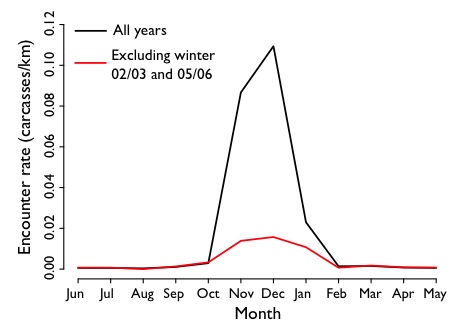

The graph shows the chance of finding a beached phalarope along the outer coast of Washington and Oregon throughout the year. It is the month-averaged (or mean) encounter rate in carcasses per kilometer. The black line shows the seasonal pattern using all of the COASST data, from 2001 to 2015. The smaller red line takes out the winter (November to January) of two years (2002-2003, and 2005-2006) when there were wrecks of phalaropes. What’s interesting is that even with the big years removed, the pattern in time is virtually the same.

With the peak years excluded (focus on the red line), the chance of finding a phalarope is highest in December – but the average survey would have to be 60 kilometers to have a serious chance of finding one. That’s a lot of walking!

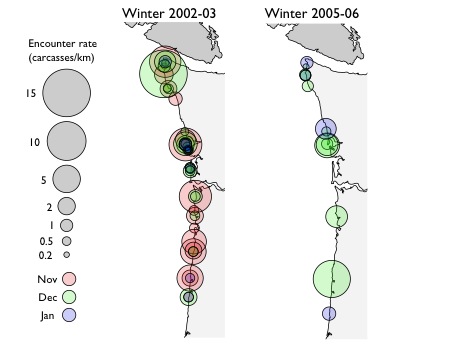

In some years, Red Phalaropes seem to run out of gas, and they can be found in abundance if your monthly survey happens during the “carcass-fall” of these tiniest of birds. In 2002-2003, a phalarope wreck lasted from November through January. Carcasses were found all along Washington and Oregon coastlines. The carcass-fall that year was 60-100 times normal and some extreme sites found up to ~15 birds per kilometer (or 1,000 times the non-wreck normal peak!!) A smaller wreck occurred in the winter of 2005-2006. It started slightly later (in December), and fewer COASSTers recorded birds, even though the total number of COASST sites was higher.

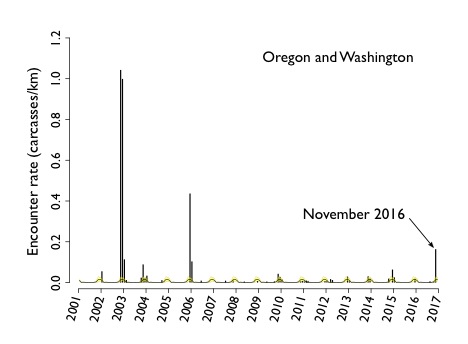

This year we’ve been getting wind of disoriented, emaciated phalaropes coming to shore in British Columbia. Although initially speculated to be associated with an oil spill, birders from Ketchikan, Alaska to Monterey Bay, California have reported seeing numbers of these birds unusually close to shore. And the COASST data have spiked up. Take a look at the very latest COASST data compared to those earlier wreck years.

With all of the changes in the coastal ecosystems of Alaska and the lower 48, we’re not sure what to expect this winter. But here’s the early warning for outer coast COASSTers in the lower 48 to be on the lookout for phalaropes, particularly following storms.