What do sea turtles, sharks, sturgeon, and rockfish all have in common? Dr. Selina Heppell, marine fisheries ecologist and a professor in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at Oregon State University, would tell you that these marine creatures all have long lifespans, mature at a late age, and are threatened by over-harvest and habitat loss (the typical story of a top predator). COASST Intern, An Huynh, had the opportunity to ask Selina some questions about her research.

Heppell uses computer models and simulations (i.e. some pretty complex math) to assess how their populations change in response to environmental factors and applies those results to aid conservation and management decisions. Her passion for marine biology takes Heppell all over the world: to teach conservation of biodiversity in the sea in Iceland, help international partners develop sustainable fisheries policies in the Mediterranean, work with high school teachers in Mississippi.

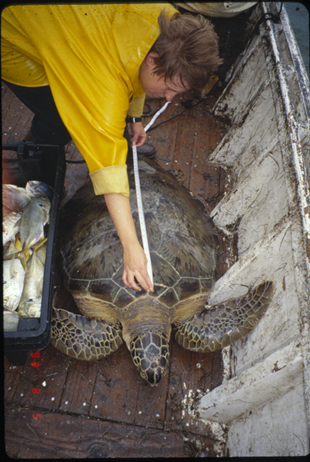

A native to the Pacific Northwest, Selina dove into marine biology early, as a volunteer at the Seattle Aquarium when she was only 12. Her sense of wonder and amazement continues, “I love to tell people about cool stuff in the ocean.” So what’s the coolest thing she’s learned? “Sea turtles have finger-like projections in their throats to help them retain and swallow food while spitting the water back out. Unfortunately, it also means that that they can’t throw up very easily – whatever goes in has to pass all the way through. This is one reason why plastic bags and balloons are a big problem for them!” As COASST expands into marine debris, we’re lucky to have Selina’s expertise on our advisory board, as we examine which characteristics make certain debris harmful to specific marine species/species groups.

Even if you eliminated the marine debris threat, Sea turtles aren’t “out of the woods,” so to speak. Marine turtle populations are also highly sensitive to bycatch, or unintended fisheries take. Although protective measures have been put into place to mitigate bycatch effects (e.g. modifying trawl nets with “turtle excluder devices”), it still takes a long time to see a response in sea turtle populations. Due to this delayed response time, there are growing efforts to monitor sea turtles in the ocean instead of just protecting them on the beaches where they nest.

Besides her field/at-sea time, as a professor, Selina spends a bunch of time with graduate and undergraduate students at Oregon State University’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. Does all the field “work” in her lab involve snorkeling at tropical locales? Selina reminds our youngest COASSTers that the road to becoming a marine scientist is hard work: “it’s a discipline that relies on rigorous data collection and evaluation of evidence.” (COASSTers have some familiarity with the difficulty of evaluating evidence, on a small scale, using the keys, measurements and photos in the Beached Birds guide). Far from a “Discovery Channel degree,” prospective students “need to be dedicated to learning the scientific method and how to contribute data and results to conservation problems objectively,” adds Selina.

Beyond the typical classroom, Heppell sees value in any projects that boost public awareness in conservation biology and marine ecosystems, “COASST is particularly valuable because it gets people thinking about what is ‘natural’ and what is ‘not so natural’ and how systems change through time over very large areas.” After many years of involving and engaging the public through lectures, teacher workshops and citizen science programs, for Selina the benefit to marine conservation efforts is two-fold, “getting people to think about connections in nature can help marine conservation indirectly, and/or directly through political action or contributions to conservation and science efforts.”