Updated March 7, 2022 – check for the latest summaries posted here

What happened?

Japan‐flagged container ship Apus, operated by the Ocean Network Express (ONE), was sailing from China to California November 30 – December 1, 2020 when it encountered severe weather several hundred miles northwest of Midway, HI. 1,816 marine containers were lost overboard.

Some released their contents, while others without buoyant cargo or insulation may have sunk intact. At least 64 of these containers were estimated to include potentially hazardous materials.

Rare massive discharges of debris in accidents like this one (or during natural disasters such as the 2011 earthquake in Japan) pose a potential danger to marine ecosystems, but they also provide unique opportunities to track debris and better understand transportation patterns and impacts.

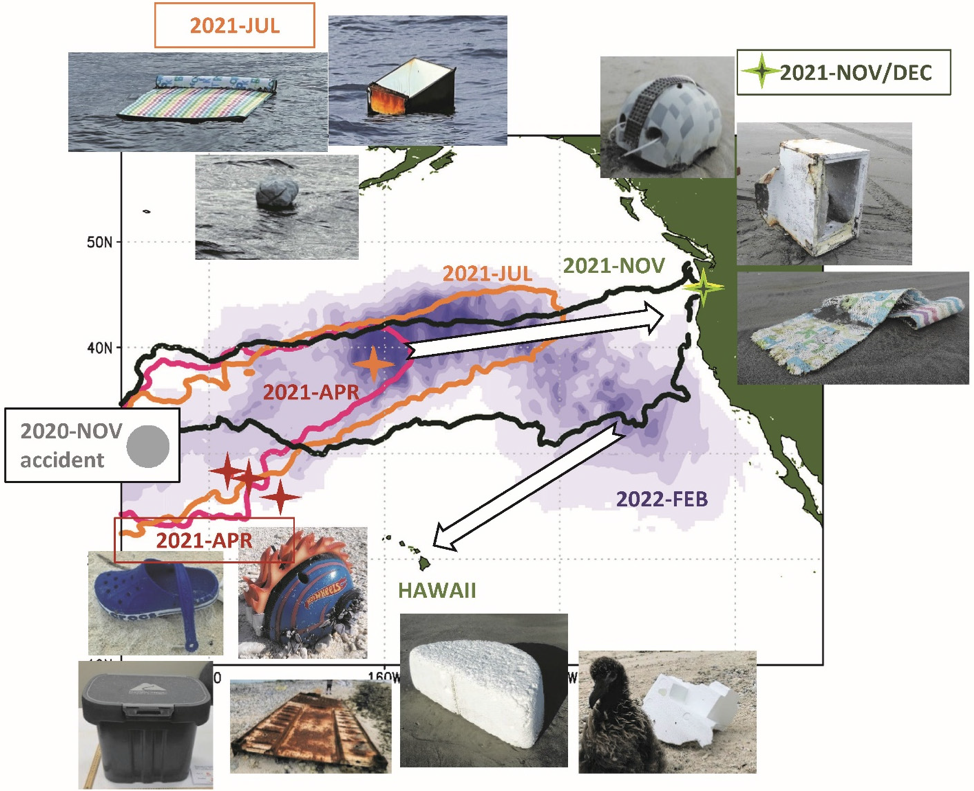

“Drift” models developed by the UH International Pacific Research Center team (which were used to successfully predict the drift of debris following the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan – see video clip below) have been useful to model the invisible path of debris from the November 2020 container spill. In a model like this one, items with high ‘windage’, might drift faster across the ocean basin. These items float high in the water column, and are strongly impacted by wind (as well as ocean currents).

The map below comes from a similar model, instead predicting the path of objects from the container spill.

With wind and oceanographic conditions in mind, the model has been able to track debris items from the source location of the spill (gray dot, left center) to locations where debris has been sighted at different times (star symbols). Debris washing up in an expected time and place based on the model is one way we can confirm that the container spill is the source of individual items.

The first thing we can see in this map is that much of the debris from the lost containers is likely still circling the Pacific ocean basin between Hawaii and the West coast (purple-blue clouds below, as of February 2022).

Future predictions from this model are indicated with white arrows. As the Pacific Gyre continues its clockwise circulation pattern, we expect that the debris cloud on the east side of the basin will migrate south and west to deposit debris in Hawaii early summer 2022 and along the US west coast in summer 2022.

How can you help? Report!

In the first months after the spill, no debris was reported. But in early 2021 observers on the Northwestern Hawaiian islands began to report ‘fresh’ debris items washing ashore in large numbers.

You can report items that seem unusual on your beach especially if they appear in large numbers OR if they match one of the categories of known Apus ONE debris depicted below. Note: these photos are only general guidance, as the contents of the lost containers is not fully documented.

Your data will help us to understand long‐range transport of various types of floating debris and improve its modeling.

To submit a report:

- If possible, take photos including a scale ruler and the whole debris item, as well as zoomed-in detail snapshots of the weathering, logo/brand, language clues, and biofouling.

- Note the date, time, and location of your observation.

- Estimate or measure the debris if no scale ruler is available.

- If you are a COASSTer – simply email your notes and photos to coasst@uw.edu. We will get that data submitted for you! If you see this type of debris on your regular debris survey, submit your data as usual and shoot us an extra email to let us know to look out for container spill debris.

- If you aren’t a COASSTer you can either:

- email maximenk@hawaii.edu to figure out an easy submission method OR

- submit directly to this Google Drive folder. Create a new subfolder (example: “2022‐03‐15 John Smith”), select who it can be shared with and upload your notes and high‐resolution photos.

Keep an eye out for:

Foam

Including pieces from broken boxes and insulation panels

Play mats

These cushioned surfaces for children float high on the water and have been spotted both on land and at sea.

Freezers and mini-fridges

Metal pieces are already rusted and many are fragmented. These have been found both floating at sea and washed up on land.

Helmets

Many varieties! Little wear and weathering on these mostly-plastic items.

Plastic foam shoes

Casual, highly-buoyant footwear (like crocs!) has washed up like-new on beaches.

Volleyballs – Wilson brand

These balls have been found in a less-than-fully-inflated state, for easy packing and transportation.

Coolers

High quality coolers in excellent condition.