A recent spate of Black-footed Albatross finds along the north outer coast of Washington in May and June got us wondering about these majestic birds.

With a wingspan of two meters (!) or longer, albatross are the largest members of the Tubenose Foot-type Family (Procellariidae). In the North Pacific there are three species: the dark-bodied, dark-billed Black-footed Albatross; the light-bodied, Laysan Albatross with a “smokey eye”; and the larger, Short-tailed Albatross, distinguished from Laysan and Black-foots by an over-sized bubblegum pink bill (plumage of Short-tails varies with age).

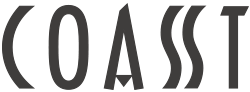

What else might a COASSTer mistake an albatross for? Bald Eagles, Brown Pelicans, Great-blue Herons and Sandhill Cranes are all COASST finds with overlapping wingspans. But each of these birds can easily be distinguished by foot-type, and bill size and shape.

A long-lived, monogamous bird, albatross begin breeding at age 5-10, and it takes two parents to raise a single chick. New pairs may require a few years of practice to “get it right. After that, mates meet annually for a long breeding season: courtship and “re-acquaintance time” starts in November, eggs appear before the turn of the year, and chicks don’t fledge until mid-summer!

Like all members of the family, albatross have a keen sense of smell and can literally smell their prey from tens of kilometers away, a talent that suits these open ocean birds. Dinner for an albatross? Neon flying squid, flying fish eggs (tobiko in sushi restaurants), and a range of small fish and shrimp-like organisms that come to the surface of the ocean at night.

Unfortunately, smelling their way to food puts albatross in harm’s way. Fishing vessels smell like floating restaurants, attracting albatross and their smaller relatives – shearwaters and Northern Fulmars – some of which become entangled or hooked in gear. Marine debris can also be deceptively appealing, as some plastics, after floating in the marine environment, adsorb and emit the same chemical (dimethyl sulfide) used by procellariiforms as a cue to identify prey. Not only that, floating debris can look like albatross prey (could you tell the difference between a squid mantle and a red lighter floating at the surface?). Young birds are especially susceptible. Dependent on their misled parents for food, chicks ingest plastics, filling their stomachs with indigestible objects they cannot regurgitate.

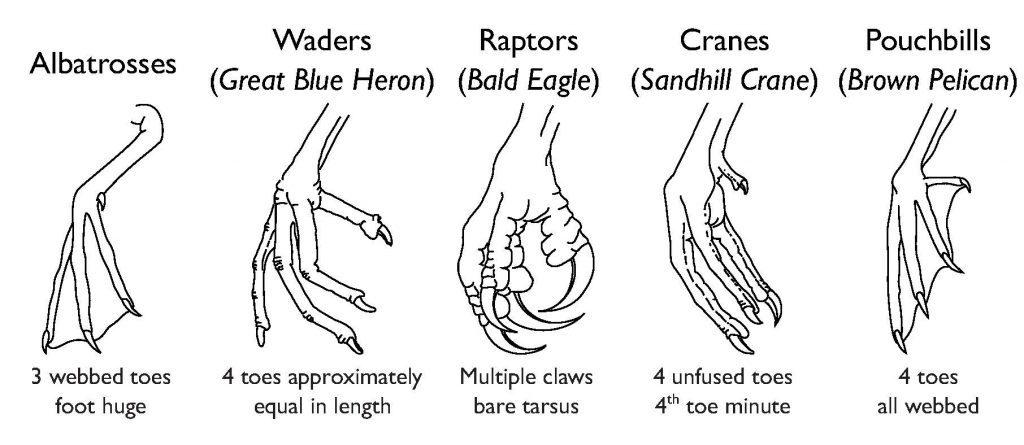

Populations of Black-foots and Laysans number in the hundreds of thousands. In contrast, Short-tails number less than ten thousand and are listed as “vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

With a body that mimics a glider, albatross have the ability to soar tremendous distances. Even while breeding on islands in the Hawaiian Island chain (Laysan and Black-foots) or southern Japan (Short-tails), breeding adults regularly visit North American waters. Laysan’s appear to prefer coastal Alaska, whereas Black-foots fly due west to the Lower 48.

Breeding so far from our shores, and preferring the open ocean, you might think COASSTers would never find an albatross. Not so! In fact, Black-foots are among our top 30 species. Peak Black-foot deposition is in the summer: May through August, just when adults are finishing breeding and chicks are coming off the colonies. But the annual pattern is “irruptive.” That is, in some years COASSTers are much more apt to find an albatross than in others. In northern Washington, 2012 and 2017 were break-out years; in southern Washington, 2003, 2007 and 2012 were big. The good news is that there doesn’t seem to be any trend towards higher numbers.

Across the COASST dataset, albatross species wash up exactly where you would expect them to given at-sea sightings: Black-foots along the West Coast, and Laysan along the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. Although the total body count favors the lower 48 (note only 3 Laysan have been found in Alaska), it’s actually the encounter rate (carcasses per kilometer) that is important. Remember, there are many more COASSTers along the outer coast of Washington, Oregon and California than there are in the Aleutian Islands! The photographs in the figure above are scaled to species-specific encounter rate the—the chance of finding an albatross in the Aleutians is about the same as along the outer coast of Washington.

A closer look at Black-foot deposition pattern on the West Coast reveals two distinct aggregations: one associated with the entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca (we’re guessing these birds are associated with the Juan de Fuca eddy – an oceanographic feature south of the Strait), and a second larger aggregation surrounding the Columbia River. Both the eddy and the “plume” of river water exiting the Columbia River into the Pacific Ocean are highly productive locations where a hungry chick or exhausted post-breeding adult can hunt pelagic prey.

Moral of this story? If you hope to see an albatross on a COASST survey, head to the south outer coast of Washington during the summer and take a stroll along the sand.