Avian influenza is a large family of viruses found around the world in more than 100 species of wild birds. The viruses are found within bird intestines and infected birds transmit them to others through fecal droppings, saliva and nasal discharges. Not all of these viruses are deadly to birds (highly pathogenic), but densely congregating birds (those who gather together) are most at risk once such a strain emerges. Thus far, wild birds have played a minor role in the fast spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses. While the viruses originate from wild birds, the spread mostly happens once a virus is within populations of human reared animals, like commercially farmed chickens, which are moved around the country by humans.

There are no known cases

of transmission of avian

influenza from beached

birds to humans.

Wild waterfowl are known to carry avian influenza strains, with most infected birds not showing outward signs of the disease. That said, not all wild birds are left unscathed. In recent years, outbreaks of HPAI on marine bird colonies in the North Atlantic have sickened and killed many birds, even putting some populations at risk of local extinction. In the Pacific Northwest, an outbreak of HPAI at a Caspian Tern colony cut the number of nesters in half.

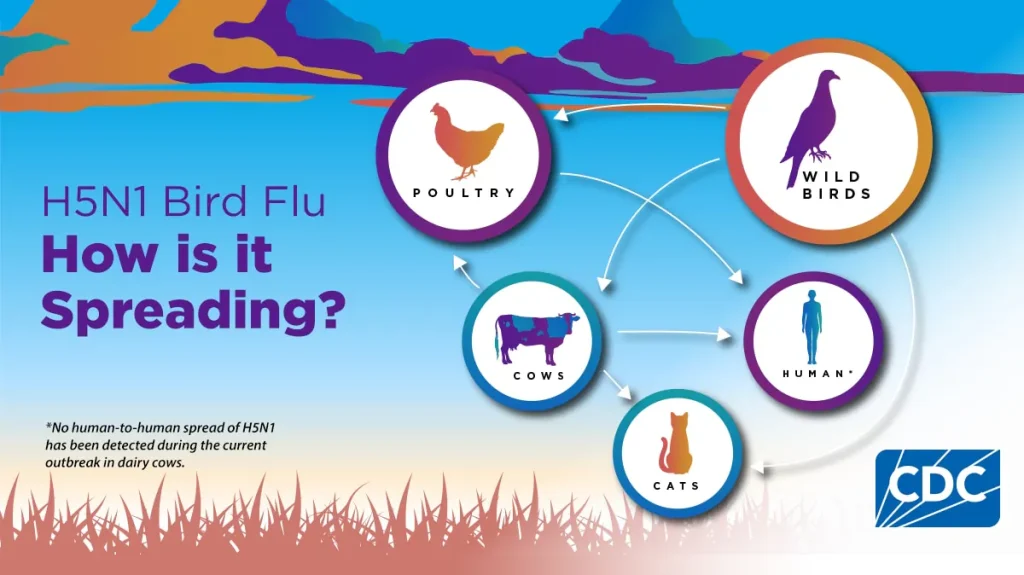

Since 1997, a particularly virulent strain of HPAI bird flu known as H5N1 has emerged. This strain heavily affects domestic poultry and has resulted in the death and culling of millions of domestic birds. Most recently this strain has leaped to other farm animals, including cows. Cats, both large cats (zoo animals) and house cats, have also been sickened. Animal to animal transmission is through contaminated droppings or eating raw contaminated meat. Unlike COVID, bird flu is not transmissible through the air.

Flu viruses have a long history of leaping from one species to another, including to humans. The swine flu pandemic in 2009 and 2010 is an example.

As of January 2025, there have been 67 confirmed cases of H5N1 in the U.S. human population; 63 of these (94%) were people working with dairy herds or on poultry farms where these agricultural animals became infected in mass numbers. The vast majority of farm workers who came into direct, prolonged contact with these infected herds or flocks (~14,000) did not manifest any symptoms. Of those with symptoms leading to testing (660), only 10% (64) had bird flu. Most of these people infected with the virus reported mild symptoms, but there has been one death (a person with underlying medical conditions who contracted the disease from caring for sick and dying birds in their backyard).

Because of low transmission rates even in highly infected situations (such as a worker on a poultry farm culling thousands of sickened birds), and no recorded person-to-person transmission, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) currently ranks the public health risk of bird flu as “low” even for the HPAI strain known as H5N1.

Is handling beachcast marine birds an activity that would be considered high risk?

There are no known cases of transmission of avian influenza from beached birds to humans. Even though the internet AI reports possible transmission from handling dead birds, all human cases have been restricted to situations in which people had prolonged contact with sick and recently killed birds, as is the case for poultry farm workers culling infected flocks.

Of course, if any COASSTer came upon many, many carcasses, or carcasses alongside sickened, struggling birds in the surf zone, then immediately take extra precautions, including staying away from live, sick birds, and calling COASST.

Finally, know that there are proven ways to protect yourself as you interact with beached birds or any deceased wildlife you may encounter on your survey. These are the things we teach all COASSTers to do as a basic part of the survey protocol:

- Always have PPEs, or personal protective equipment. You don’t need a hazmat suit, but you definitely need rubber or latex gloves to form a barrier between yourself and the organisms you are handling. COASST recommends kitchen gloves because they are sturdy, come up past the wrist, and can be easily washed with soap and hot water after your survey is finished. If you’re using disposable gloves, make sure you have multiple pairs, in case you need to swap them out.

- Even if you have access to hot water and soap, it’s a good idea to take alcohol gel to disinfect gloves, hands, and measuring equipment.

- Select who will be the bird handler and who will be the “pencil” before you start surveying to minimize the chance of contamination. If surveying solo, take your measurements and photos first, get a good look at the bird, and then remove gloves and disinfect your hands before filling out the rest of your data sheet without needing to touch the bird again.

- Bird handlers – Make sure that your hair is secure, your hat is on tightly and watch out for dangling scarves! Don’t brush your face with your gloved hands. If you need to readjust during a survey, take your gloves off, and use a squirt of alcohol gel or a wet-wipe to clean your hands before touching your face.

- Wearing a mask can reduce the chance of contracting respiratory illnesses (those that reside in the lungs), but it will not prevent bird flu, because this virus is not spread through aerial transmission.