Common Murres (Uria aalge) are one of the most fascinating marine birds in the North Pacific. As adults, these “footballs with wings” can fly as easily under the water as they can on land. Murres have been found diving as deep as the continental shelf (~200m), zooming around after forage fish and krill. Especially during the breeding season, it takes two parents fishing for most of each day to sate the demands of their single hungry chick. One of the reasons is because parents bring back one fish at a time, and always head in, tail out.

Fortunately for the parents, young murres leave the colony after a scant three weeks. Early in the evening, as the sun tips below the horizon, a murre chick will leave the safety of the colony and walk to the edge of the cliff, accompanied by the male parent. Dad and chick often engage in an extended conversation – it’s impossible to watch and not pretend that Dad is giving his chick a last few bits of advice.

Well heeded! A murre chick actually fledges before its wings have grown flight feathers. Essentially a fuzzy tennis ball with winglets, these chicks take a leap into the unknown. Will they hit the water, or the rocks below? Turns out that it doesn’t matter. Although you might think this is a “dinosaur waiting to happen” survival strategy, the worst imaginable (a splat) doesn’t happen. Instead, young murres bounce on the rocks, pick themselves up and run for the waves, avoiding marauding gull predators on the way.

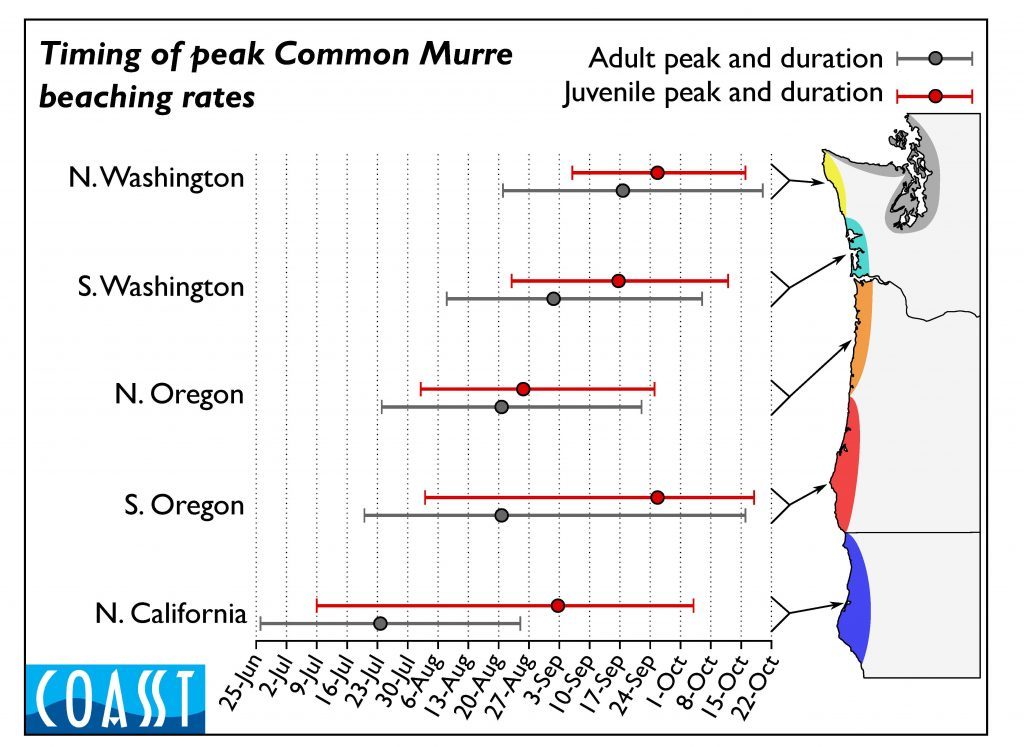

Once safe on the water, each chick begins calling loudly: Cheep! Cheep! Cheep! If you’re within sight of a murre colony, it’s a sound you can hear from the mainland during the fledging season (July in California and Oregon; August/September in Washington, British Columbia and Alaska). And it’s a good thing fledglings have a loud voice because they’re announcing their presence to Dad, who returns the call with a guttural: Eh! Eh! Eh! Eh! Eh!

They will spend the next several weeks together, until the fledgling learns to fish. Of course this is an especially dangerous time: pairs can get separated and storms can make fishing difficult. COASSTers know that the post-breeding period is the time to expect murres to wash up on the beaches. And this got us wondering, is there a signal in the beached bird data that might tell us something about how successful breeding was on the colonies?

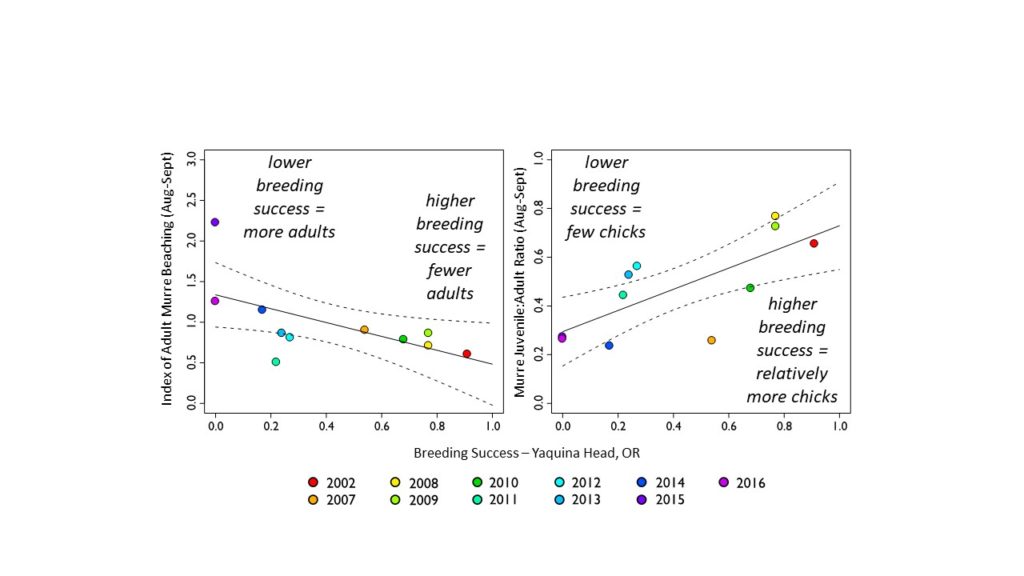

To figure that out, we turned to Rob Suryan, Associate Professor at Oregon State University, who maintains a long-term database on the Common Murre colony at Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area, immediately north of Newport, Oregon. Rob and his team spend the early summer in the Yaquina lighthouse surveying the murre colony and counting the eggs, then chicks, then fledglings. This gives them a measure of the breeding success of each pair: the average number of fledglings per pair. Given that murres only raise a single chick, the very highest this number could ever get is 1.0 (if every single pair was successful). In reality, something above 0.70 signifies a good year. In poor years, numbers below 0.40 are common.

We reasoned that in a really good year, colonies would produce a lot of fledglings, filling the nearshore with Dad-chick pairs. And COASSTers might see that signal on the beach as more than the usual number of juvenile murres, because juvenile mortality is always higher than adult mortality.

By contrast, in poorer years, fewer chicks would even reach fledging stage, and adults would likely be stressed and thinner, more susceptible to the ravages of early fall storms. In these conditions, COASSTers might see relatively more adults. That is, both relatively more than juveniles, and absolutely higher encounter rates than “normal” years.

Turns out, we’re right! The graphs below show the relationship between breeding success on the Yaquina Head colony (on the horizontal, or X axis), and measures of COASST data (on the vertical, or Y axis). Each point is a different year, colored so you can easily find each one.

What does all of this mean? Basically, that beached bird data can stand in as a proxy for breeding success on the colony. And this is really good news, because most of the murre colonies in the Pacific Northwest are not regularly monitored, either because they are too far from shore to see (like the Yaquina colony), or because the island or spire where the murres nest is literally unscalable.

If you’re a Pacific Northwest outer coast COASSTer, take special care on your late summer and fall surveys – your murre data are showing us that death is part of the life of the ecosystem.